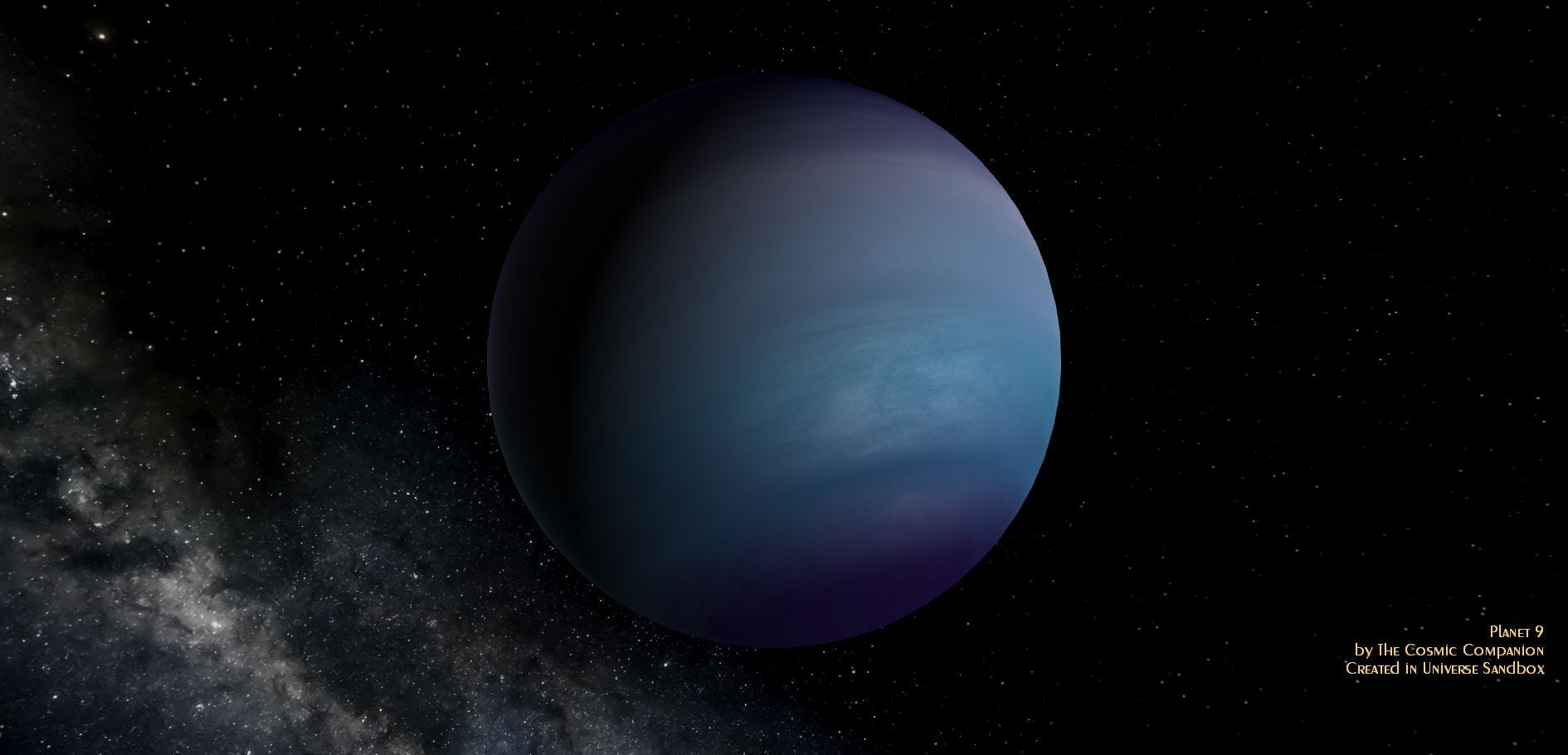

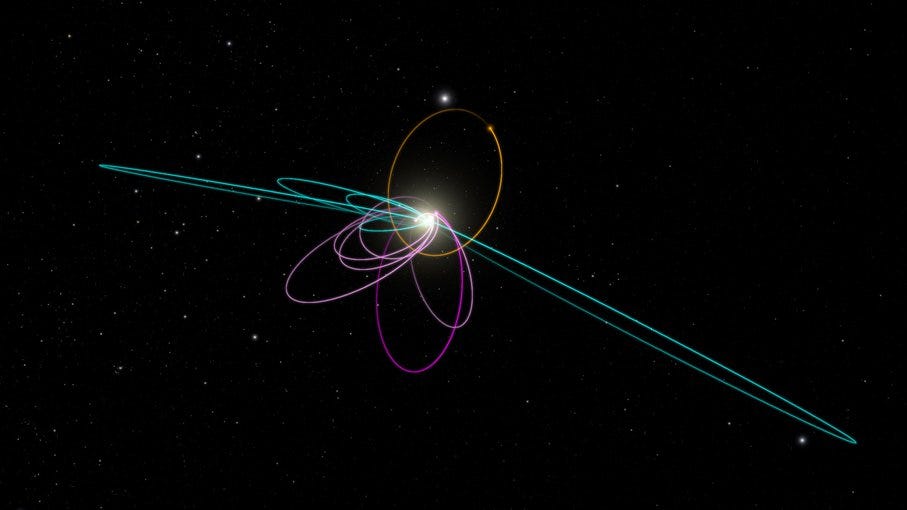

Uranus was first seen in 1781, and seventy years later, astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi announced his discovery of an “eighth planet,” orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. This object, Ceres, was found to the largest member of the main asteroid belt, and was classified as such in 1851. At that point, the solar system was said to contain 13 planets (including Neptune, first seen in 1846), and the number of recognized planets was reduced to just eight members. In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto, known for decades as the 9th planet. This distinction lasted until 2006, when Pluto was “demoted” to the class of dwarf planets. However, Ceres was also named to this group, recognizing its unique characteristics. Despite its classification of Pluto as a dwarf planet, it is now recognized as the first Trans-Neptunian Object (TNO), and the first member of the Kuiper Belt, ever found. Today, we know of many minor bodies beyond Neptune — 316 were recently discovered in just a single study. Unlike Pluto, gravitational interactions in the outer solar system strongly suggest that planet nine, should it be found, is likely to be far too massive to be a dwarf planet like Pluto. “Although we were initially quite skeptical that this planet could exist, as we continued to investigate its orbit and what it would mean for the outer solar system, we become increasingly convinced that it is out there. For the first time in over 150 years, there is solid evidence that the solar system’s planetary census is incomplete,” explains Dr. Konstantin Batygin, Professor of Planetary Science at Caltech. Further investigation revealed six of the bodies had nearly identical pulls on their orbits, including being drawn to a gravitational well located 30 degrees below the plane along which the planets travel. A mass of objects, called the Kuiper Belt, orbits at the edge of our solar system. This band of objects includes Pluto, the first Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) found by astronomers. The researchers first postulated that a number of Kuiper Belt objects huddled together, creating the gravitational pull. But, that theory was quickly rejected when calculations showed that the belt would need to be 100 times more massive than it is to account for observations. Further investigation revealed that a more massive planet could cause this effect, provided it is aligned so that the most distant point in its orbit (apogee) is opposite the point where other planets reach their apogees. The pull of such a world could also explain the unusual orbit of a large Kuiper Belt object called Sedna, researchers found. “If you want to put a number on it, I’d be somewhere like 80 percent sure that there’s a Planet X out there… I don’t think it’s a slam dunk; it’s not 100 percent, because it’s such low-number statistics, But there are a lot of strange things that seem to be going on that would be explained quite well with there being some kind of massive planet out there,” said Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science. It is possible that long ago, as the giant worlds of our solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, were forming, a fifth massive world also took shape. Gravitational interactions with the massive planets may have then flung this unknown world to the depths of the solar system. Although astronomers know the rough path that this theoretical world should trace, there is little indication of where it may currently be found in its orbit. If it is at its most distant point in its orbit, only the largest telescopes in (and above) the Earth have any chance of seeing it. However, if it is closer to the Sun, several instruments may be able to record its presence — it may already be imaged, unrecognized in data collected during other observing sessions. “I would love to find it. But I’d also be perfectly happy if someone else found it. That is why we’re publishing this paper. We hope that other people are going to get inspired and start searching,” said Brown, who discovered the dwarf planet Sedna in 2003. Doubts still persist as to whether or not this world exists, or if another cause could be behind the odd orbits drawn out by objects in the depths of the solar system. The coming years will bring in a flurry of new observational data about Kuiper Belt Objects, either pointing astronomers to Planet 9, or down the road toward a new theory. Amateur scientists who want to help find this world (assuming one awaits discovery), can join in the search using Backyard Worlds: Planet 9. Participants could go down in history as the person who discovered one of the largest planets in our solar system. “All those people who are mad that Pluto is no longer a planet can be thrilled to know that there is a real planet out there still to be found. Now we can go and find this planet and make the solar system have nine planets once again,” Brown declares. This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here. Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.