But EV uptake brings its own set of challenges. While the UK’s national energy provider has assured consumers that there is “definitely enough energy” to facilitate mass EV adoption, the problem lies in how to sustainably and cheaply supply cars with power. Our local networks were not designed to charge millions of cars with energy simultaneously and, as we move towards a zero-carbon electricity system with variable wind and solar generation, the energy may not be there when we need it most. The key to handling this lies in ensuring EVs are able to affordably charge when there is plenty of wind and sun-driven energy available. Coordinating this requires significant planning and government investment into a smart charging network.

How to charge

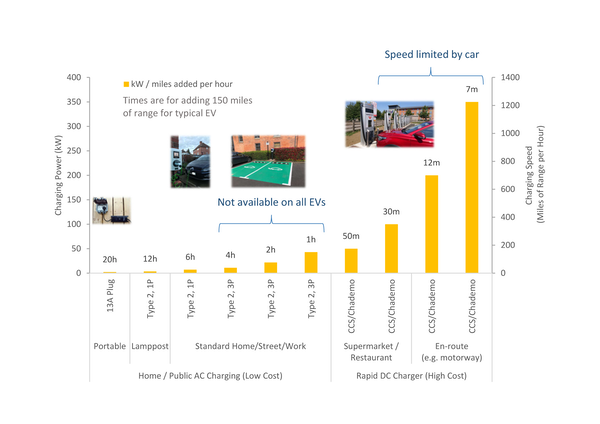

When we decide how to charge an EV, a key consideration is the vehicle’s “dwell time” at its charging location. If the driver is at home for the night or at work for the day – and therefore in no rush to charge – they can use a seven kW charger, a standard home charger in the UK, to charge their car for a week’s driving (about 250km) in an eight hour session. But if the driver decides to charge their car on the same charger while they pop to the supermarket for just 45 minutes, they’ll only get around 30km of extra range: barely enough for a day’s driving. Dwell times and charging speeds In the latter situation, a “DC Rapid” charger – which typically provides between 50 to 150kW – is more appropriate. While they are far more expensive – typically at least ten times the cost of a standard home charger – you get what you pay for: using these chargers will provide roughly a week’s driving in just 45 minutes. The problem with these rapid charges is that, as well as being expensive, they place large demands on electricity infrastructure which could lead to local blackouts. Since, on average, cars spend about 95% of their time parked, you’d ideally want them to be slowly charging from excess renewable energy during that time, with rapid charges reserved for long road trips and occasional emergency charges. In future, cars might also help support their local electricity grid by discharging power at times of high demand when renewable generation is low – a technology known as “vehicle-to-grid”. To enable this technology, communication between chargers and cars needs to be a two-way street, allowing drivers to simultaneously charge up and support the grid.

Energy inequality

Access to power is also a financial issue. For those with off-street parking at home, staying plugged in is easy, but many don’t have that option. That means plugged-in households will have access to low-cost travel, whilst those without home charging will face higher costs due to expensive street charging. In the UK, around 7 million households, many on lower incomes, fall into the latter group. We must widen access to charging not just to help the grid, but also to reduce social inequity. Street chargers could be automatically assigned to the car owner’s account when they plug in, enabling those without home charging to access a full range of services for the same cost as someone with a home charger. In the UK, we’d need about 750,000 street chargers to ensure that those without home chargers can charge once a week. If we want to make use of the energy storage in those cars to help balance production and consumption from the grid – and to achieve the UK’s net zero target – I’d estimate we’d need up to 5 million chargers. That would require 500 new street chargers to be installed every day between now and 2050. Using our cars to help balance our grid will likely be cheaper than energy storage alternatives like pumped-storage hydroelectricity or liquid air storage, since we already have some of the infrastructure we need. But to make this happen, car manufacturers, network operators and energy suppliers – and the UK government – must coordinate to put the right chargers in the right places at the right time. This article by Rachel Lee, PhD Candidate in Electric Vehicle Usage, University of Sheffield, is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.