To many, escooters seem like the vital cog in last-mile mobility solutions in urban areas. They’re highly accessible, environmentally friendly, affordable, and there’s plenty of variety to choose from. Just this morning, I counted four different brands blocking the sidewalk in my street. I feel like in 2021 we were just starting (at least in Europe) to see escooters transition from something that drunk people and teenage boys ride short distances for kicks, to a legitimate form of short trip transport. But deaths, accidents, injuries, and escooters crowding the pavement have resulted in a year of crackdowns and regulation that shows no sign of abating.

Cities forced to respond to escooter accidents and casualties

In November, Paris introduced new rules for hire escooters to be limited to speeds of 10 kmph throughout the capital, with only a few areas remaining limited to 20 kmph. It followed an accident where a pedestrian was hit and killed by an e-scooter. Nordic countries have also struggled with escooter deaths and injuries throughout 2021. As a result, many cities reduced the number of escooters available on the streets. In Sweden, one cyclist died after crashing into an e-scooter parked across a cycle path. A hospital in Helsinki told Euronews Next that it had hired an additional doctor to cope with the extra burden of scooter-related injuries.

The UK shows the pain for micromobility providers

Since June 2021, escooters have been available under a UK rental trial in a number of London boroughs (private scooters are banned from roads, sidewalks, and bike paths). However, a UK study by the Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety (PACTS) found that from the beginning of 2021 to November, there were almost 300 injury-collisions within the UK. This included nine fatal and 91 serious injuries (including 31 head injuries). It’s unclear how many of these were hire escooters vs. illegal escooters. If this wasn’t all bad enough, just this month, in a PR nightmare, privately owned escooters were banned on all Transport for London services after an exploding battery caused a fire on a busy tube service. It’s currently illegal to use private escooters on roads, bike paths, or sidewalks in the UK, so people were presumably taking them to private land to ride. That’s going to mess up a lot of people’s Christmas presents this year who were planning to go offroad.

Micromobility providers underestimate the risks

One thing I’ve consistently heard when I’ve asked escooter companies informally if they teach people how to ride escooters is that “it’s easy, just hop on and go!” Yet riding an escooter is hugely different from a moped or bicycle, especially in steering and balance. One study surveyed people in escooter accidents that resulted in hospitalization — 40% of subjects’ injuries were from their first ride! That’s hardly an endorsement for repeat business.

Regulations are inconsistent and confusing

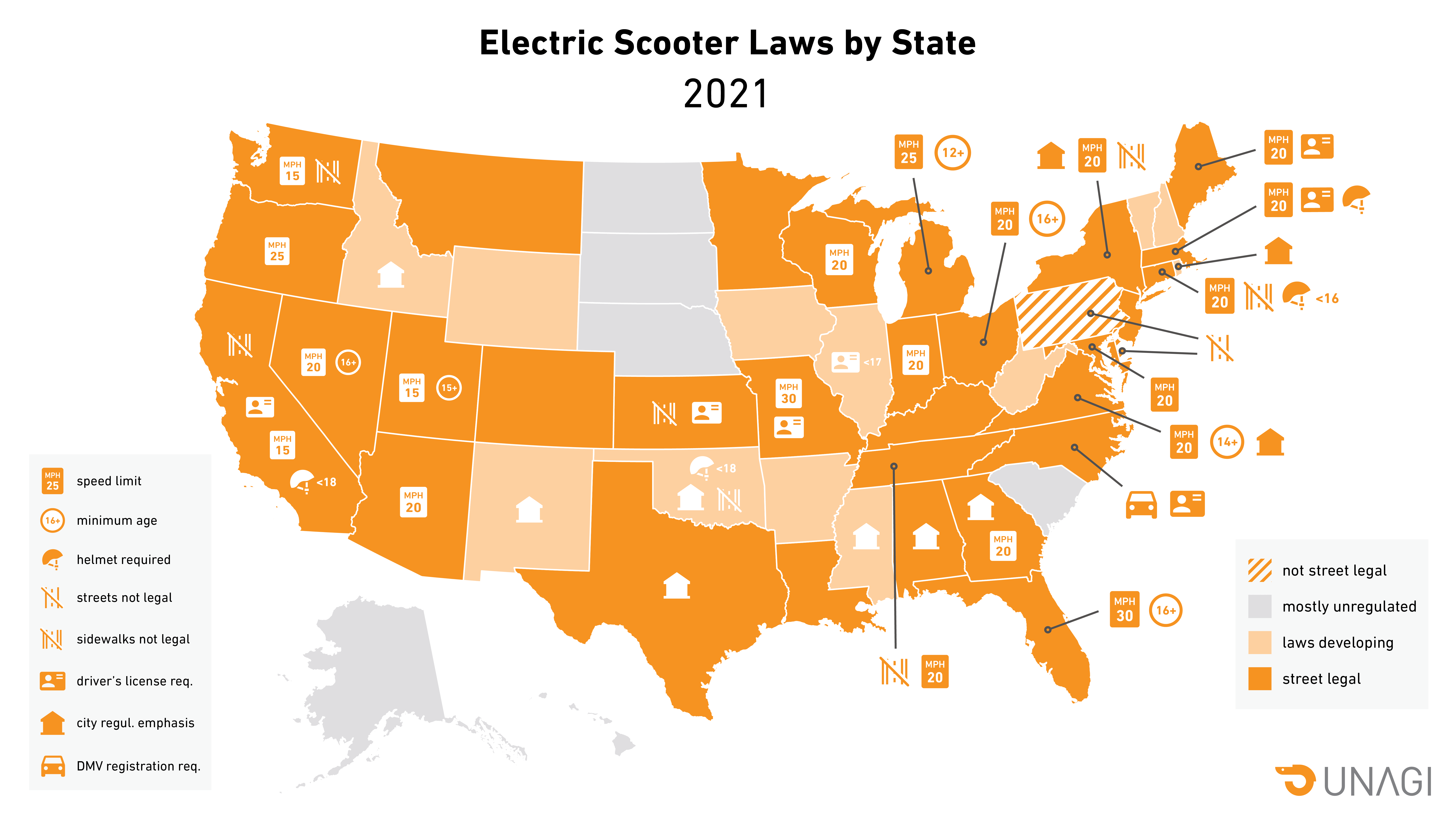

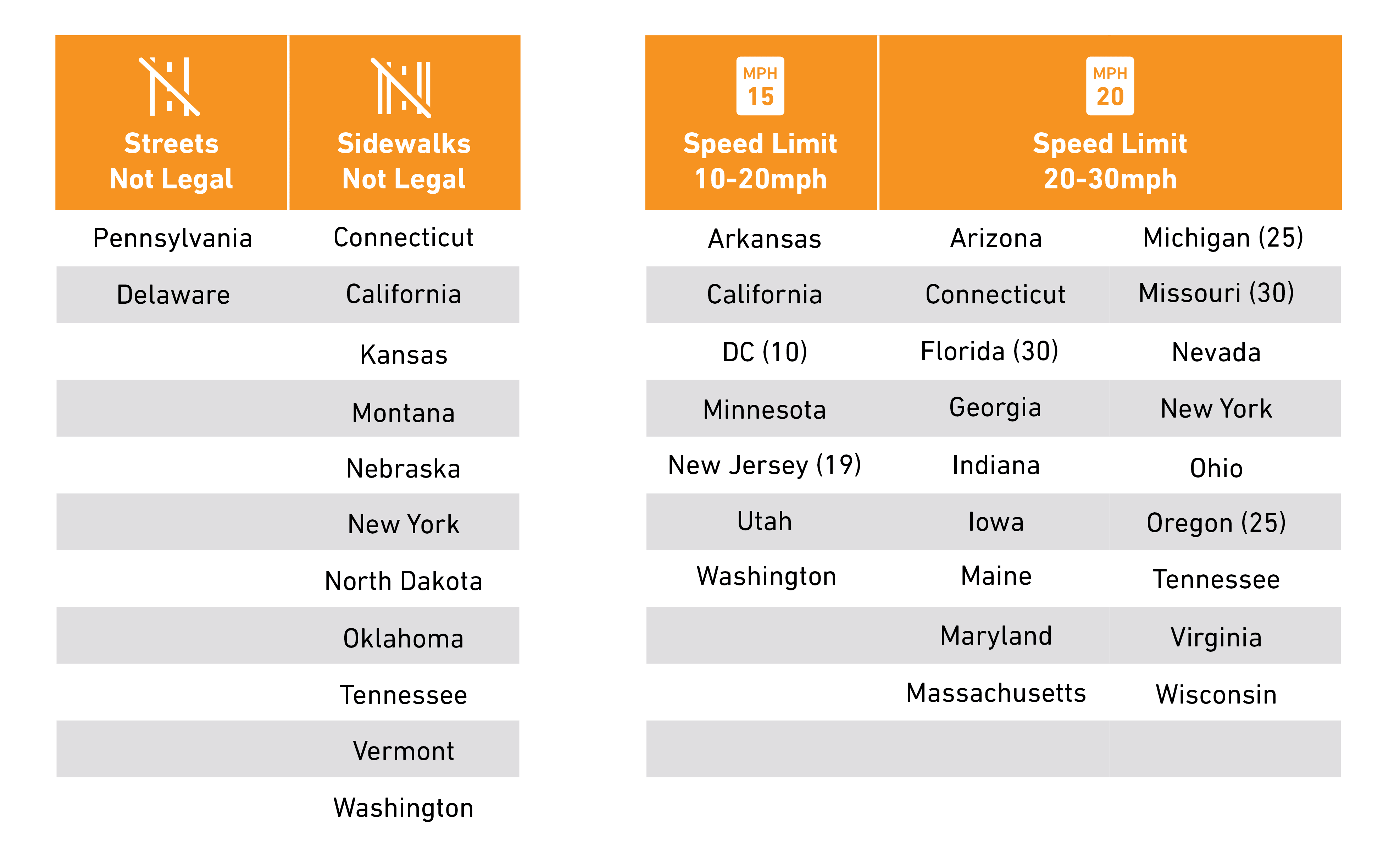

America is like the holy grail for many in micromobility in terms of the size of the population in urban areas. However, there’s still a mismatch of regulations on a state-by-state basis in terms of rider age, the need for a driver’s license or helmet, speed, and legally rideable locations in the US. This makes it challenging for escooter companies to plan and market mass country campaigns effectively.

Did bike riding ever receive the same level of policing as escooters?

No, biking has been around a hell of a lot longer than scooter riding and existed long before automobiles. Unsurprisingly every year there are more riders, but also more injuries, and more deaths in comparison to escooters. Further, the movement has benefitted from widespread fitness and health endorsement and the creation of infrastructures like bike lanes, traffic prioritization like bicycle traffic lights, and dedicated bike parking spaces. While these have in part benefited the rollout of escooters, they’re a long way from ameliorating their perceived shortcomings. It’s hard to compare like with like. Escooters are less used than bicycles (electric or otherwise), and their novelty factor makes them more visible. Visibility means easy prey for members of the public who might traditionally overlook a tipped-over bicycle.

Cities say no

In May, the City of Toronto unanimously voted to uphold a ban on escooters on public streets, bike lanes, sidewalks, pathways, trails, and other public spaces. They attributed this to their commitment to safety and accessibility for people, especially seniors and those living with disabilities, in Toronto by voting not to opt-in to the provincial e-scooter pilot. Then, last month the City of Miami placed a temporary ban on escooters, halting a pilot project for about a week. However, they’ve returned with a commitment to more oversight around hours of operation, speed limits, and other safety measures. It shows that safety and accessibility remain a pain point for cities struggling to develop a solution.

How much responsibility can micromobility companies take for fuckwits?

To be clear, I don’t blame the escooter companies themselves, especially in terms of micromobility hires. These companies work really hard to build relationships within cities with town planners, safety advocates, and disability groups. They’ve also deployed tech to police non-compliant rider behavior such as parking outside designed areas, One of the leaders of this is Supedestrian. They are embedding their escooters with software to detect dangerous behavior such as riding on the sidewalk, going the wrong way down a one-way street, and aggressively swerving. The software can slow down and stop rides autonomously and alert riders to rule violations. There’s also the ability to generate collision reports in the event of a crash. Every day I see people double riding like this on the streets of Berlin:

Can’t tech find a solution? Sensors and load-bearing, perhaps? I think it will be a bumpy ride for escooter and micromobility companies in 2022. I’ve interviewed a bunch to get their take — stay tuned to read all about it.