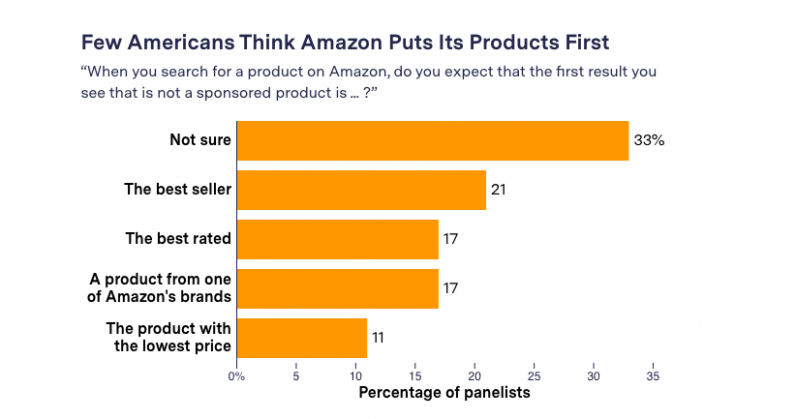

That’s not what shoppers expect.

Invisible tags

“If basically you’ve got somebody with market power that is restraining competition both in terms of site access or where things appear on the site,” he said, “that is potentially problematic.” Congress is considering a package of anti-monopoly bills aimed at big tech, including the Ending Platform Monopolies Act, which would make the practice of platforms giving their brands a leg up explicitly illegal.

‘They would shut us down’

“If the customers are not seeing [our products] in the top five offers, then it makes it really hard for us to reach customers,” said Gabriela Mekler, a Miami mom who co-founded the organizational products company Mumi in 2014. “Their product will always show before yours,” Mekler said. “We’re a small company,” she said. “They would shut us down.” But when The Markup asked to speak to some of the sellers the group had quoted anonymously, NAW’s vice president of government relations, Blake Adami, demurred.

‘This was a knockoff’

Dering said he wasn’t worried about losing sales because Peak Design mainly targets wholesalers and customers who want a high-end brand. Still, he said he found the move “highly distasteful.”

Hard to spot

Large brick-and-mortar retailers also have house brands. Costco has Kirkland Signature. Target has Up&Up, among others. Historically, he said, when large stores create brands they have been clearly affiliated with the store. “Unlike a retail store where you see everything on the shelf, the platform may be in a position to elevate its goods in a way that is harder to do in a retail outlet,” said Baer, the former FTC official, and assistant attorney general at the Justice Department. “Consumers don’t even know what’s missing,” she said. “When that happened, we realized we couldn’t even compete,” he said. He decided not to launch the product. It launched in 1995, with the goal of becoming “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore.” Four years later, it declared its intention to become “Earth’s Biggest Selection.” “We’re like, what are you talking about? You guys sell books,” he said. “What do you mean you’re selling sporting goods?” They sold the business.

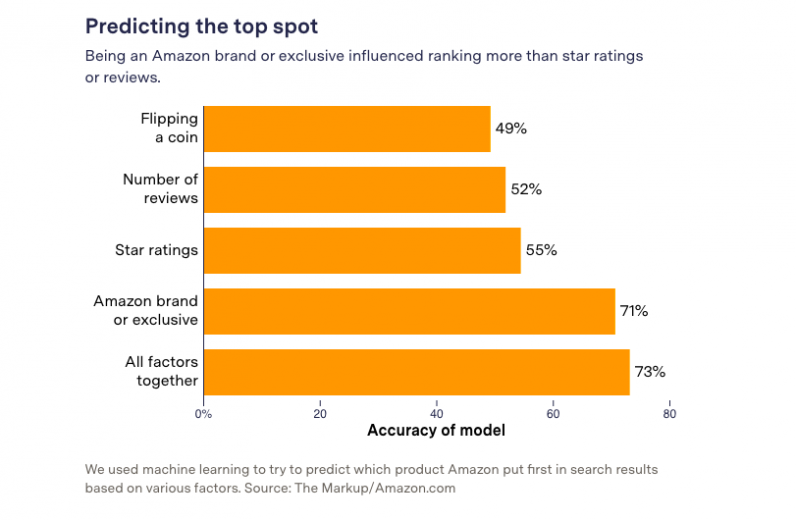

A leg up

“We would use that for all of our products from the get-go for the first six months or longer,” he said. Once a new house brand product was established, Meng said employees would turn off search seeding. “Without fail, your product would drop in ranking,” he said, “but the hope was that it would drop a small amount.” “You turn off the ads and you lose organic rank within days,” Boyce said. “It’s pay to play.” Lots of companies are paying. We found that inside the search results alone, 17 percent of products were paid listings. That doesn’t include entire rows of sponsored products that appear as special modules on about a third of search result pages. (Including those would roughly double the ad percentage on the first results page.)

Struggling for visibility

“If you’re willing to spend a ton of money, you can sell a ton of product,” said Evan Patterson, vice president of business development at California-based Linco, which is one of Boyce’s clients. “Our search ranking has improved dramatically,” Patterson said. But it still has a ways to go. When The Markup searched for “caster wheels” at the time of writing, Linco appeared in the middle of the fifth page. This article was originally published on The Markup by Adrianne Jeffries and Leon Yin and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.